Concurrency in Go

Concurrency in Go, makes Go programming language very unique and attractive compared to other languages, in this section I am going to share the notes which I took when I was watching coursera video series.

If you did not already check previous post on Go, it could be helpful to check it out first.

Specialization serie is Programming with Google Go

Keep in mind that the notes are taken from several resources mainly from the course, however post may include other resources as well, I have referenced them when required, if nothing is referenced then it means, notes are taken from the course.

Paralel Execution

- Two programs execute in paralel if they execute at exactly the same time

- At time

t, an instruction is being performed for bothP1andP2.

Why use parallel execution

- Tasks may complete more quickly

- Example: Two Piles of dishes to wash

- Two dishwashers can complete twice as fast as one

- Some tasks must be performed sequentially

- Example: Wash dish, dry dish

- Must wash before you can dry

- Example: Wash dish, dry dish

- Some tasks are parallelizable and some are not

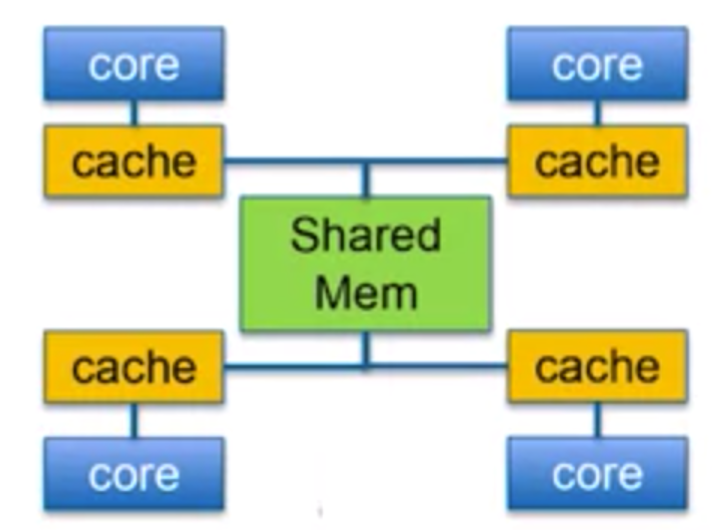

Von Neumann Bottleneck

Speedup without Parallelism

- Can we achieve speedup without Parallelism ?

- Design faster processors

- Get speedup without changing software

- Design processor with more memory

- Reduces the Von Heumann bottleneck

- Cache access time=1 clock cycle

- Main memory access time = ~100 clock cycles

- Increasing on-chip cache improves performance

Moore’s Law

- Predicted that transistor density would double every two years

- Smaller transistors switch faster

- Not a physical law, just an observation

- Exponential increase in density would lead to exponential increase in speed

Power Wall

Power / Temperature Problem

- Transistors consume power when they switch

- Increasing transistor density leads to increased power consumption

- Smaller transistors use less power, but density scaling is much faster

- High power leads to high temperature

- Air cooling (fans) can only remove so much heat

Dynamic Power

P = a * CFV^2ais percent of time switchingCis capacitance (related to size)Fis the clock frequency- V is voltage swing (from low to high)

- Voltage is important

- 0 to 5V uses much more power then 0 to 1.3V

Dennard Scaling

- Voltage should scale with transistor size

- Keeps power consumption and temperature, low

- Problem: Voltage can’t go too low

- Must stay above threshold voltage

- Noise problems occur

- Problem: Does not consider leakage power

- Dennard scaling must stop

Multi-Core Systems

P = a * CFV^2- Cannot increase frequency

- Can still add processor cores, without increasing frequency

- Trend is apparent today

- Parallel execution is needed to exploit multi-core systems

- Code made to execute on multiple cores

- Different programs on different cores

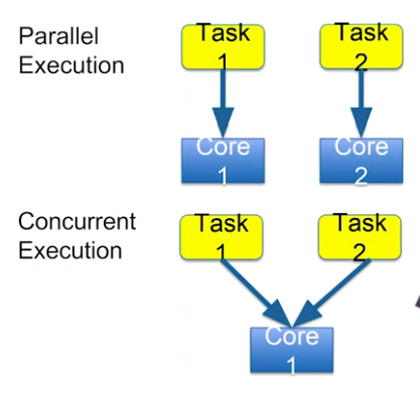

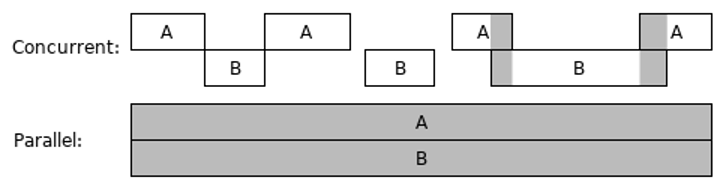

Concurrent vs Parallel

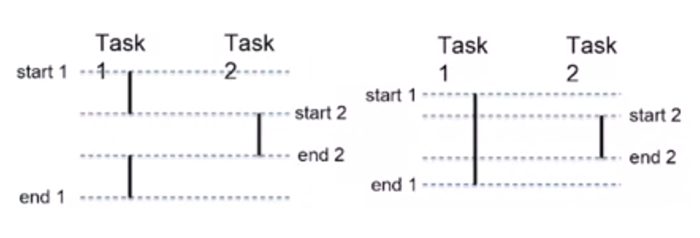

Concurrent Execution

- Concurrent execution is not necessarily the some as parallel execution

- Concurrent: start and end times overlap

- Parallel: execute at exactly the same time

- Parallel tasks must be executed on different hardware

- Concurrent tasks may be executed on the same hardware

- Only one task actually executed at a time

- Mapping from tasks to hardware is not directly controlled by programmer

- At least not in go

Concurrent Programming

- Programmer determines which tasks can be executed in parallel

- Mapping tasks to hardware

- Operating system

- Go runtime scheduler

Hiding Latency *(Crucial)

Concurrency improves performance even without parallelism

Tasks must periodically wait for something

- i.e. wait for memory

- X = Y+Z read Y,Z from memory

- May wait 100+ clock cycles

Other concurrent tasks can operate while one task is waiting

Concurrent programming is useful even no paralelism

Hardware Mapping

- Programmer does not determine the hardware mapping

- Programmer makes parallelism possible

- Hardware mapping depends on many factors

- Where is the data ?

- What are the communication costs ?

Concurrency Basics

Processes

- An instance of a running program

- Things unique to a process

- Memory

- a. Virtual address space

- b. Code, stack, heap, shared libraries

- Registers

- a. Program counter

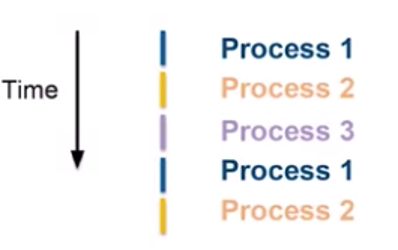

Operating System

- Allows many processes to execute concurrently

- Processes are switched quickly

- 20ms

- User has the impression of parallelism

- Operating system must give processes fair access to resources

Scheduling Processes

- Operating system schedules processes for execution

- Gives the illusion of parallel execution

- OS gives fair access to CPU, memory , etc.

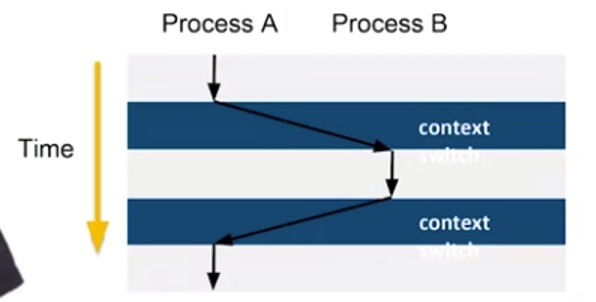

Context Switch

- Control flow changes from one process to another

- Process “context” must be swapped

- Air cooling (fans) can only remove so much heat

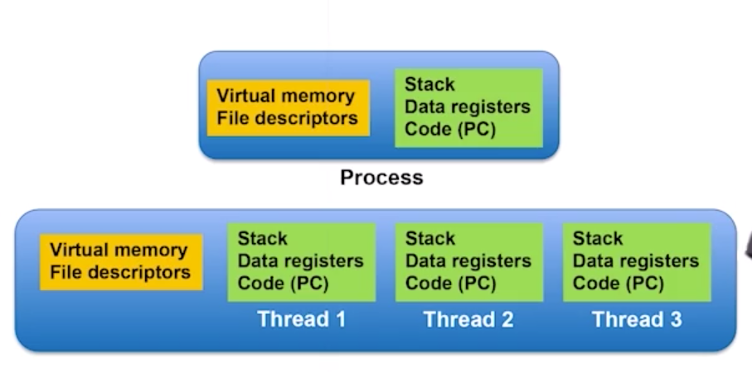

Threads and Goroutines

Threads vs. Processes

- Threads share some context

- Many threads can exist in one process

- OS schedules threads rather than processes

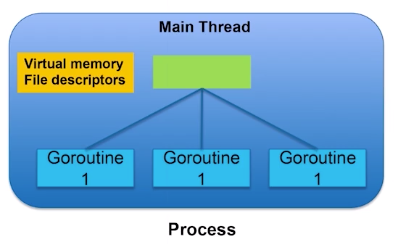

Goroutines

- Like a thread in Go

- Many Goroutines execute within a single OS thread

We can call Goroutines as lightweight threads in Go.

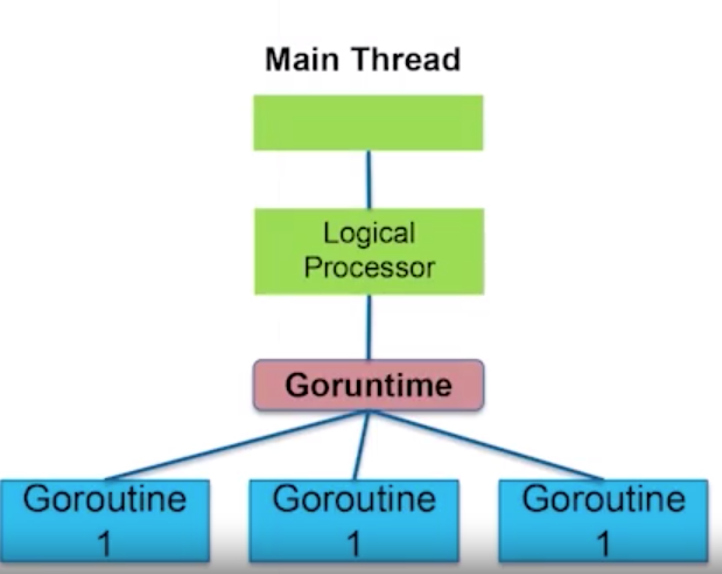

Go Runtime Scheduler

- Schedules goroutines inside an OS thread

- Like a little OS inside a single OS thread

- Logical processor is mapped to a thread

Interleavings

- Order of execution within a task is known

- Order of execution between concurrent tasks is unknown

- Interleaving of instructions between tasks is unknown

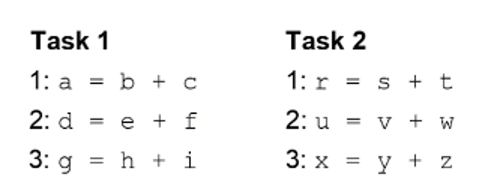

Possible Interleavings

- Many interleavings are possible

- Must consider all possibilities

- Ordering is non-deterministic

- Interleavings occurs on machine code level.

Race Conditions

It is happenning when multiple goroutines try to write/read from a source at the same time, could be prevented using mutex

- Outcome depends on non-deterministic ordering

- Races occur due to communication

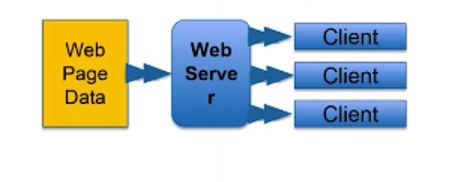

Communication Between Tasks

- Threads are largely independent but not completely independent

- Web server, one thread per client.

- Make threads for each client who are connecting to web server

- Image processing, 1 thread per pixel block

- Some level of communication can occur between threads, let’s say we want to blur the image accordingly, then the threads which are working on neighborhood pixels should communicate with each other.

Goroutines

Goroutines are new way of threading in lightweight approach.

Creating a Goroutine

- One goroutine is created automatically to execute the main()

- Other goroutines are created using the go keyword

package main

func main () {

a=1

foo()

a=2

}

func foo() {

// does something ...

}

- Main goroutine blocks on call to

foo()

package main

func main () {

a=1

go foo()

a=2

}

func foo() {

// does something ...

}

- New goroutine created for

foo() - Main goroutine does not block

Exiting a Goroutine

- A goroutine exits when its code is complete

- When the main goroutine is complete, all other goroutines exit

- A goroutine may not complete its execution because main completes early

Early Exit

func main() {

go fmt.Printf("New routine")

fmt.Printf("Main routine")

}

- Only “Main routine” is printed

- Main finished before the new goroutine started

Delayed Exit

func main() {

go fmt.Printf("New routine")

time.Sleep(100 * time.Milisecond)

fmt.Printf("Main routine")

}

- Add a delay in the main routine to give the new routine a chance to complete

- “New RouteMainRoutine " is now printed

Timing with Goroutines

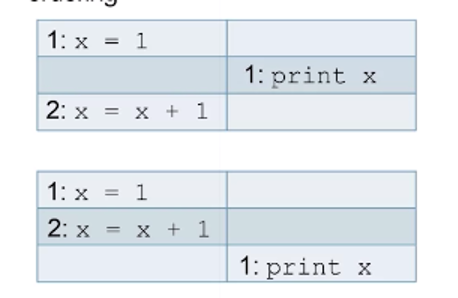

- Adding a delay to wait for a goroutine is bad !!

- Timing assumptions may be wrong

- Assumption: delay of 100 ms will ensure that goroutine has time to execute

- Maybe the OS schedules another thread

- Maybe the Go runtime schedules another goroutine

- Timing is nondeterministic

- Need formal synchronization constructs

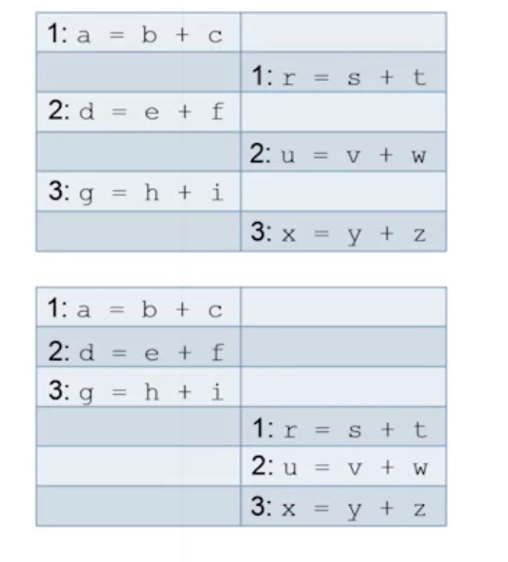

Synchronization

- Using global events whose execution is viewed by all threads, simultaneously

- Want print to occur after update of x

Example

| Task 1 | Task 2 |

|---|---|

| x=1 | |

| x=x+1 | |

| GB | if GB print x |

- GLOBAL EVENT (GB) is viewed by all tasks at the same time

- Print must occur after update of x

- Synchronization is used to restrict bad interleavings

Threads in Go

Threads in Go are generally handled using wait groups

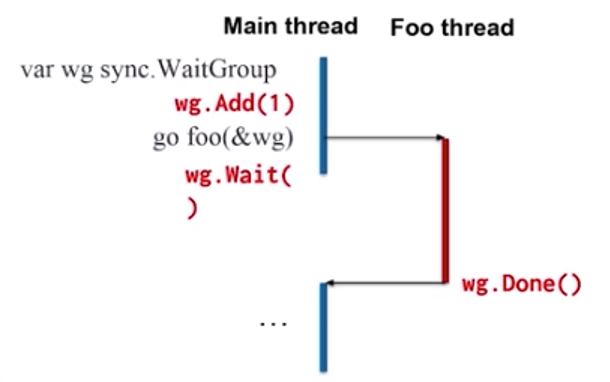

Sync WaitGroup

- Sync package contains functions to synchronize between goroutines

- sync.WaitGroup forces a goroutine to wait for other goroutines

- Contains an internal counter

- Increment counter for each goroutine to wait for

- Decrement counter when each goroutine

- Waiting goroutine cannot continue until counter is 0

Using WaitGroup

Add()increments the counterDone()decrements the counterWait()blocks until counter == 0

Example

func foo(wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

fmt.Printf("New routine")

wg.Done()

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(1)

go foo(&wg)

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("Main Routine")

}

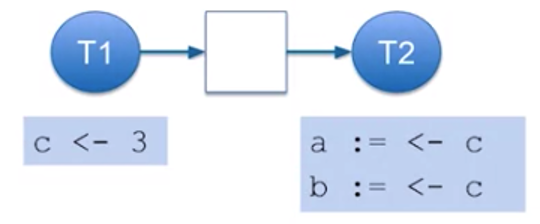

Goroutine Communication

- Goroutines usually work together to perform a bigger task

- Often need to send data to collaborate

- Example : Find the product of 4 integers

- Make 2 goroutines, each multiplines a pair

- Main goroutine multiplies the 2 results

- Need to send ints from main routine to the two sub-routines

- Need to send results from sub-routines back to main routine

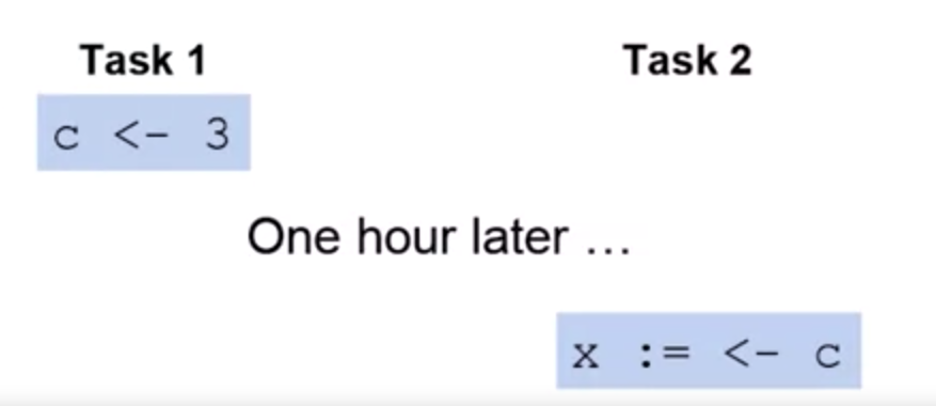

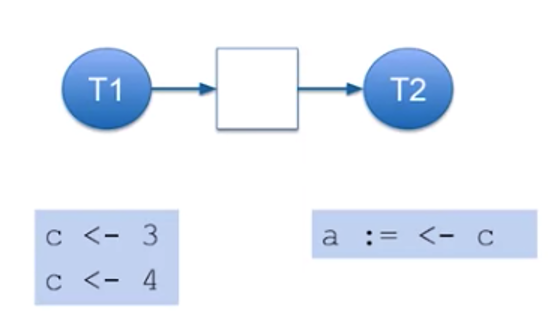

Channels

- Channels are used to make communication between goroutines

- Channels are typed

- Use make() to create a channel

c:=make(chan int)

- Send and receive data using the <- operator

- Send data on a channel

C < - 3

- Receive data from a channel

x:= <- c

Example

func prod(v1 int, v2 int, c chan int) {

c <- v1*v2

}

func main() {

c:=make(chan int)

go prod(1,2,c)

go prod(3,4,c)

a:= <-c

b:= <-c

fmt.Println(a*b)

}

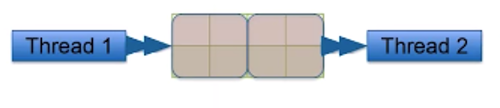

Unbuffered Channel

- Unbuffered channels cannot hold data in transit

- Default is unbuffered

- Sending blocks until data is received

- Receiving blocks until data is sent

Blocking and Synchronization

- Channel communication is synchronous

- Blocking is the same as waiting for communication

- Receiving and ignoring the result is same as a Wait()

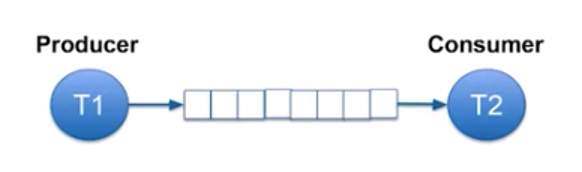

Buffered Channel

Channel Capacity

- Channel can contain a limited number of objects

- Default size 0 (unbuffered)

- Capacity is the number of objects, it can hold in transit

- Optional argument to make() defines channel capacity

c:=make(chan int, 3)

- Sending only blocks if buffer is full

- Receiving only blocks if buffer is empty

Channel Blocking, Receive

- Channel with capacity 1

- First receive blocks until send occurs

- Second receive blocks forever

Channel Blocking, Send

- Second send blocks until receive is done

- Receive can block until first send is done

Use of Buffering

- Sender and receiver do not need to operate at exactly the same speed

Adding a channel to our goroutine

Note that in this section notes are taken from: https://www.sohamkamani.com/blog/2017/08/24/golang-channels-explained

- A channel gives us a way to “connect " the different concurrent parts of our program.

- Channels can be thought of as “pipes” or “arteries” that connect the different concurrent parts of our code

Directionality

out chan <- int `

- The chan<- declaration tells us that you can only put stuff into the channel, but not receive anything from it.

- The int declaration tells us that the “stuff” you put into the channel can only be of the int datatype

- Although they look like seperate parts, chan<-int can be thought of as one datatype, that describes a “send-only” channel of integers.

- Similarly, an example of a “receive-only” channel declaration would look like:

out <- chan int

A channel can be declared without giving any directionatility, which means it can send or receive data.

Bi-directional channel can be created using following “make” statement

out :=make(chan int)

After this section, notes are taken from: https://go101.org/article/channel.html if you prefer to have deep dive into channels, you may visit there.

Concurrent computations may share resources, generally memory resource. There are some circumstances may happen in a concurrent computing.

In the same period of one computation is writing data to a memory segment, another computation is reading data from the same memory segment. Then the integrity of the data read by the other computation might be not preserved.

In the same period of one computation is writing data to a memory segment, another computation is also writing data to the same memory segment. Then the integrity of the data stored at the memory segment might be not preserved.

These circumstances are called data races. One of the duties in concurrent programming is to control resource sharing among concurrent applications, so that data races will NOT happen. The ways to achieve this duty are called concurrency synchronization, or data synchronization. GO supports several data synchronization techniques. The following section will introduce one of them, channel.

Other duties in concurrent programming include:

- Determine how many computations are needed

- Determine when to start, block, unblock and end a computation.

- Determine how to distribute workload among concurrent computations.

Most operations in Go are not synchronized. In other words, they are not concurrency-safe. These operations include value assignments, argument passing and container element manipulations. There are only a few operations which are synchronized, including the several to be introduced channel operations below.

DO NOT COMMUNICATE BY SHARING MEMORY, SHARE MEMORY BY COMMUNICATING *(THROUGH CHANNELS)

Channel Types and Values

Like array, slice and map, each channel type has an element type. A channel can only transfer values of the element type of (the type of) the channel.

Channel types can be bidirectional or single-directional. Assume T is an arbitrary type,

chan Tdenotes a bidirectional channel type. Compilers allow both receiving values from and sending values to bidirectional channels.chan <-Tdenotes a send-only channel type. Compilers do not allow receiving values from send-only channels.<- chan Tdenotes a receive-only channel type. Compilers do not allow sending values to receive-only channels.

T is called element types of these channel types.

Values of bidirectional channel type chan T can be implicitly converted to both send-only type chan <-T and receive-only type <-chan T , but not vice versa (even if explicitly). Values of send only type chan<-T cannot be converted to receive only type <-chan T.

Each channel has capacity. A channel value with a zero capacity is called unbuffered channel and a channel value with a non-zero capacity is called buffered channel.

For more detailed explanation on channels you can visit https://go101.org/article/channel.html

Take care ! 👋🏻

Maybe next time, topics could be revisited by examples 😉